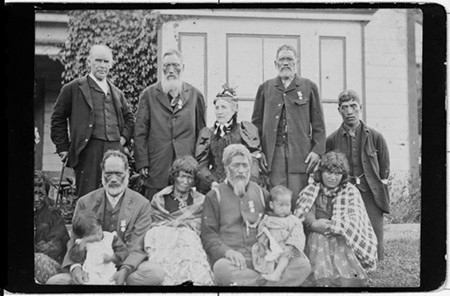

Group portrait including Thomas Bevan (back row, left) and Ropina (seated, left).

Margaret Clark nee Bevan is seated back row centre.

Clark, Garry Trevor, fl 1981-1984 :Photographs of early Manakau. Ref: 1/2-057399-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22490109

Background

In June 1845, nine year old Thomas Bevan (1836-1913) his younger brother Will and older sisters Mary and Margaret, walked from Port Nicholson, Wellington, to Waikawa, some six miles from the Otaki river crossing. They were led on their journey by a Maori guide, Ropina. The journey took six days and on the first night, they overnighted with the Wall family, at The Halfway House.

In 1907 Thomas Bevan’s memories were published as The Reminiscences of An Old Colonist [1907], My arrival in New Zealand – ‘How four pakeha children travelled from Port Nicholson to Waikawa in 1845’

This extract is about his journey northwards along the Porirua track to The Halfway.

Introduction

The Bevan family had migrated to New Zealand, departing from London in October, 1840, on the ship Lady Nugent, arriving on the 17th March 1841.

Thomas Bevan Jnr wrote that during the voyage out, several of the family died. This included baby Nugent at nine days on 15 January, their mother on 30 January and 13 year old Henry on 4 March. Thomas Bevan Snr. was left to care for four little children.

Mr Bevan set up a rope making industry at Te Aro, however in 1844, his supply of flax dried up due to troubles along the road to Porirua. He subsequently travelled north of Otaki, to re-establish his business at Waikawa, leaving the children in the care of an Aunt.

When it seemed safe to do so, he sent for the four children and in May 1845, they were put onto a schooner to sail northwards and join him. However, there was a terrible storm on the first night and the schooner returned to harbour.

The children were meant to get back on board the next day however they were frightened and went into hiding until the ship sailed without them. As a result, their father arranged for a Maori guide to walk them to Waikawa.

Extract about the walk to Waikawa

“My father, who was a rope-maker, had brought out with him the necessary plant to carry on the business; and established a rope-walk at Te Aro in 1842.”[A ropewalk is a long straight narrow lane, or a covered pathway, where long strands of material are laid before being twisted into rope.]

“The trouble with the Natives in 1844 cut off the supply of flax, so he transferred his rope-walk to Waikawa, leaving his children in Wellington. The following year, feeling satisfied that the Native disturbances were over, he made arrangements for us to come to him...

“...The following month he despatched a trustworthy Maori to guide us up the coast to our future home. The name of our guide was Ropina. He is still living, but he is now known by the name of Tamihana Whareakaka.

“It was in June, 1845, that we four children, with our guide Ropina, started on our weary journey over the rough bush tracks from Wellington to Waikawa.

"The first day we started to climb the long forest-clad range standing above Kaiwharawhara, overlooking Port Nicholson, and we had a great struggle to ascend the hill.

“My younger brother, being too weak to walk, had to be carried most of the way in a blanket, slung from the shoulders, by Ropina. We three children followed behind. When our guide was tired he would put the child down and let him walk a little way.

“All that day we followed the steep and rough trail over the ranges, through dense underbrush and tangled supple-jacks, over prostrate logs, across swamps and streams, by rugged hill-sides, and through darkening woods—and still before us marched our watchful guide, carrying my little brother, besides his burden of blankets and food for us all.

“Ever, as he trotted along, he talked to us in his few words of broken English, cheering us on, comforting us as best he could, and calming our fears.

“No stream was there to ford, no treacherous swamp or rough place to cross, but he assisted each one over in safety; and then, resuming his heavy burden, placed himself once more at our head.

“Thus we fared on, we children bravely trying not to be afraid, and sustaining ourselves with the thought that we were going to our father.

“Our first day's journey brought us to Mr. and Mrs. Wall's house at Takapau, called in those days 'The Half-way House.' Those two kind settlers were very good to us, gave us food and shelter, and made up a bed for us in front of the fire-place.

“Next day we continued our journey along a track through dense bush to Kenepuru, Porirua, the place known in after years as" The Ferry." It took us the whole day to travel this far.

“When we arrived the soldiers were engaged in forming the Porirua road to Wellington. Our guide took us to a rude accommodation house, kept by Mrs. Jackson, a negro woman, and left us there, thinking that among people of our own race we would be well looked after.

“We were given a corner of the whare in which to pass the night, but we suffered much discomfort and fear, for the place was filled with rough soldiers, drinking and quarrelling until nearly daylight.

“We enquired anxiously for our friend Ropina, but he had gone to spend the night with his own people at a neighbouring kainga.

“The hours of darkness passed very slowly and wearily, and we were right glad when daylight returned, and with it the trusty Ropina. This night, spent among our own countrymen, was the only occasion on the whole journey when we children were not treated with all kindness and respect.

“The next day Ropina got Mr Jackson's men to ferry us across to Paremata, where the barracks of the soldiers were situated. The officer in command, on seeing us little folk and hearing that we were on our way through the hostile country to Waikawa, was greatly amazed, and at first would not permit us to proceed.

“At length our guide, through the medium of the regimental interpreter, convinced him that we could pass through in safety, and we resumed our journey.”

Several days of travelling continued until Ropina was able to deliver the young children to their father. The Bevan home was about half a mile from the pa of the Ngatiwehiwehi near the mouth of the Waikawa river. Thomas wrote - "Arriving at the pa a great cry of welcome arose from the Natives, who assembled to meet us, and then we were led by our guide to our father."

End note

Thomas lived out his life in Waikawa (near Manukau, north of Otaki). After his father died, he went farming and managed the rope walk operation, winning prizes for his rope in Dunedin, Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, Vienna and in the United States. His son, Thomas Jnr. was in the business of farming and the construction of steel cables.

Of interest, in 1875, the Drake brothers, Thomas John Drake (b1841) and Arthur Drake (b1852) left their home at the Halfway (Glenside) and moved north. Arthur settled into the old Bevan home at Waikawa and it became known as the Drake homestead. The house was constructed of pit sawn totara. It is no longer standing, however continued to be occupied by Harriet Drake after World War II.

Further information

The full publication of Thomas Bevan’s reminiscences can be read on Victoria University’s New Zealand Electronic Text Collection’.

Photographs of Thomas Bevan and Ropina (Tamihana Whareakaka) can be viewed on the National Library online collection.

Maps of Waikawa and Manukau showing places of significance including the site of the Bevan ropewalk and several Bevan homesteads are in the book Horowhenua its Maori place names & their topographic & historical background by G Leslie Adkin (1948). Wellington.

Photographs and maps of the site of the Bevan home and ropewalk are in the book Bitter Water, A story of Waikawa by Deb Shepherd and Laraine Shepherd (1999). Wellington.

A good description of the life of Thomas Bevan and the business of making rope can be read in Kete Horowhenua.